Prospective Immigrants, Please Note

How we got here: the story of my parents’ immigration from the Philippines to the United States in the 1970s.

Adrienne Rich reading her poem, “Prospective Immigrants, Please Note.” Read more of her thoughts behind the poem and find the text on billmoyers.com.

Prospective Immigrants, Please Note

I first encountered Adrienne Rich’s poem in the 2010s, when I ran a writing circle for Swirl, a group for mixed-race individuals, couples, and families. In the writing circle I focused on themes of identity and culture. We explored how to bring disparate backgrounds together, how to feel more present in one’s body as the children of two or more clashing histories.

I am not mixed-race, but as the first to be born in the United States, I am still a child of clashing histories. Not Filipino enough, not American enough. The last two lines of Rich’s poem:

The door itself makes no promises.

It is only a door.

A gut punch. A recognition that the American dream is not promised. Or that the American Dream is just that…a dream.

“Our country has many truths, but certainly one of them has to be that this was never a democracy. That this was a hope of democracy, an enormous, an enormous hope for true democracy, and that it failed many people from the outset and it’s failing more people now.”

The Hart-Celler Act

October 3, 1965. President Lyndon John signs the Hart-Celler Act into law. This law lifts quotas on immigration to the United States, which had been restricted especially from Asian countries since the 1920s. From this vantage point in history, we can say that this was the door that opened immigration from Asia.

The bill was a corrective, yes, of the racist quotas that had been in place, specifically barring Chinese, Japanese, and then Filipinos to immigrate to the U.S.

“This bill that we sign today is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives, or really add importantly to either our wealth or our power. ”

Atilano at the Manila airport, walking on the tarmac, 1975. He is in a brightly printed top and bell bottom pants. Skinny. This photo is in black and white, while all the rest from the same day are in color. I don’t know who took this. I don’t know where they took it from. He carries two bags, one visible, slung on his right shoulder. He carries a book, a towel or cloth draped from his left hand. He doesn’t smile. He wears large glasses. His hair is jet black and long, almost covering the nape of his neck.

He will turn salt and pepper soon. He will cut his hair. He will start wearing suits almost exclusively at work. He is going from a Philippine summer to Boston autumn. He will experience winter for the first time. He will experience having to do things for himself. He won’t have brothers to bring him fresh clothes or food from home. He will sleep in a call room. He will put his food on the window sill, because the Boston frost will keep it fresh.

But right now he doesn’t know any of that. What he does know: he is leaving his wife of 1 1/2 years at home. With their 8 month-old daughter. He has worked hard. He passed his exams with flying colors, the tests that would allow him to get placement in the United States. Leaving the Philippines was the common goal, was always the goal. Everyone was doing it. They finished medical school in order to leave.

Health Care & Filipino Migration

Filipinos have migrated to the U.S. in multiple waves. My parents were part of the Fourth Wave of immigration. This wave was made possible by the passage of the Hart-Celler Act and the 1976 Health Professional Assistance Act, which was created to solve shortages of healthcare providers in the U.S.

"They needed doctors. There was a need." ~ My mom ~

"They needed doctors. There was a need." ~ My mom ~

Filipino doctors and nurses were primed to fill the healthcare shortages. When the U.S. purchased the Philippines as a territory, they took over the education system. English was the lingua franca of Philippine schools (replacing Spanish) from the early 20th century.

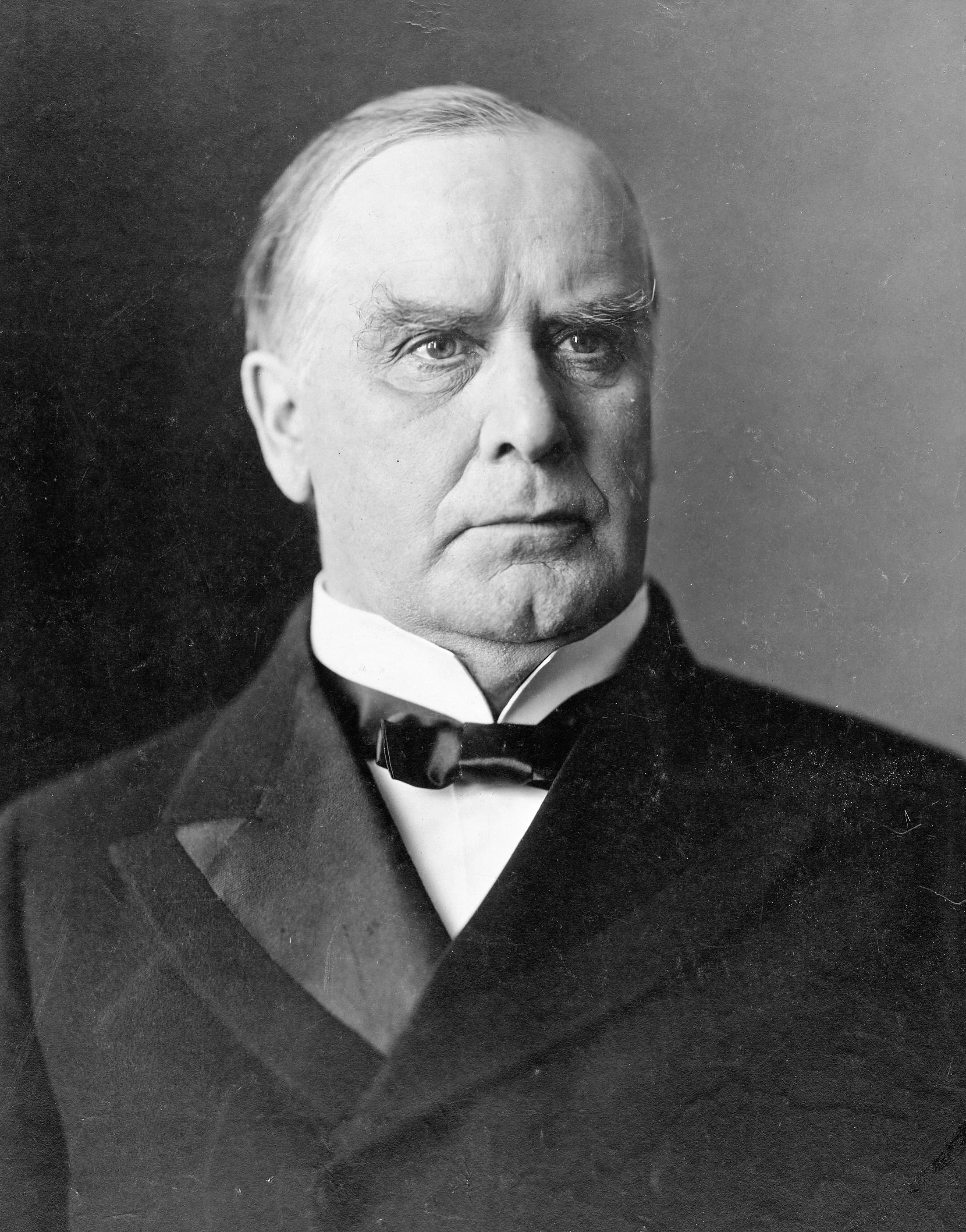

“…the mission of the United States is one of benevolent assimilation…”

President William McKinley, 1898.

After the U.S. fought alongside the Philippines for the latter’s freedom.

Upon the U.S. purchase of the Philippines from Spain.

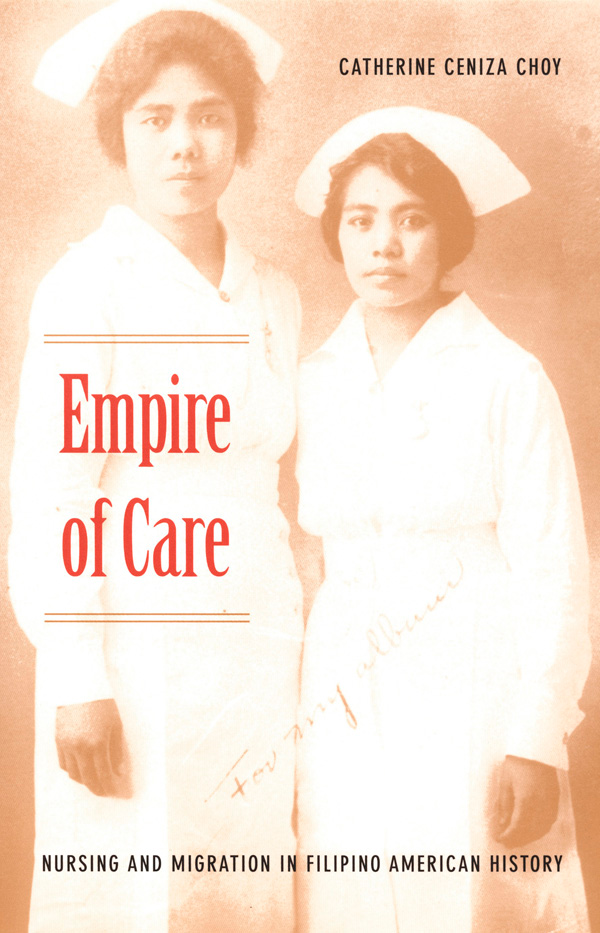

Catherine Ceniza Choy explores how the U.S. remade the educational system in the Philippines (particularly medical education) in her study, Empire of Care. In her book, she quotes less-than-benevolent attitudes toward Filipinos:

“We are practically cleaning up these Islands, left foul and insanitary and diseased by generations of hygienically ignorant peoples. We are stamping out the conflagration of disease started long before the American occupation…” – Victor Heiser, director of health in the Philippine islands

In 1976, Congress passes the Health Professions Educational Act.

“The Congress finds and declares that the availability of high quality health care to all Americans is a national goal.”

As I write this, the longest government shutdown in U.S. history (43 days) has just ended. Democrats attempted to hold out on a key issue: extending health care subsidies, without which tens of millions of Americans would see their health care costs increased. Maybe even doubled.

We’re a long way from the U.S. investing in the health of their citizens.

References & Resources

References

Lee, Catherine. 2015. “Family Reunification and the Limits of Immigration Reform: Impact and Legacy of the 1965 Immigration Act.” Sociological Forum 30 (June): 528–48. https://doi-org.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/10.1111/socf.12176.

Transcript

Carolina: They needed doctors. There was a need.

Atilano: there was a lot more prestige if you can get into a program in the States. So I went and did it in Boston, right? I was in internal medicine for two years. The last six months of the second year I started applying. I got accepted in Canada, New Jersey and Boston. But because Boston was the most prestigious of all, I decided to go to Boston. Yeah, so I was very excited. Even though on the plane ride from Manila to Boston, I was nonstop (gestures crying, tears down cheeks). (laughs) Because I was leaving Mommy and Almira, who was only eight months old then, right? We were just starting to bond, and that kind of thing. Really like being torn apart from – because our plan was to be together, but the stupid US embassy wouldn’t issue them a visa.

Amanda: So when you found out you go with him when he left, when did you think you might be able to go?

Carolina: We just kept on applying. We just kept on looking for ways to go, but they never happened.

Atilano: We had the process going the whole time. We didn't hire a lawyer, but she would go back and forth to the US consul. Yeah, it was interesting. It was difficult, it was a difficult decision. But at some level I could understand their thinking about it. And we didn’t have very good reasons, economic or whatever reasons to actually come back, you know?

Atilano: every time I came home I was a typical OFW, right? Overseas Foreign Worker. So we would have balikbayan boxes. And once or twice at customs they would open those boxes and I said – you know because, at some point when Almira was still small, I would bring home diapers, disposable diapers and take them out of the box so I can put more inside the big box. And a customs officer opened it and said can I have some of these diapers? I said no they’re for my daughter! What are you talking about?

Amanda: Do you remember packages that Mommy would send you?

Atilano: Yeah, she would send the photos. They’re not in albums. Loose photos with writing on them and dates and all of that.

Amanda: And the cassette tapes – Do you remember getting those, where Ate would sing?

Atilano: The tapes? Yeah. Or singing. She would sing – I would sing it to you too when you were little – she would sing “I will survi” and “tee-morrow.” The sun will come up tee-morrow. But she likes to, she would just spontaneously burst into song. When she was little. But because I wasn’t around then when I come home I would be the stranger. So she wouldn’t warm up to me until a few days into my visit.

Carolina: I think I joined your dad in – you were born in October in Boston. I had joined him already. But I had gone there the year before for a post-graduate course. That's how I -

Amanda: So the first, when you first went to the States -

Carolina: It was only for a post-graduate course. Like a three-week course at Harvard post-grad for psychiatry and then I came home. That was the plan, that if you went and came back then they will give you a visa because you had gone and came back. But this time to be sure that I would get there we did a diplomatic – you can't refuse a diplomatic visa. So they had to give it.

Amanda: Are you supposed to do anything with a diplomatic visa?

Carolina: I went there to have a fellowship in – my fellowship in family psychiatry and marital therapy was at Tufts University. But I was not paid by them. My boss – he just wanted me to have a placement, so they gave the training but I was not paid in the US. So it's a lot of – I guess, choices were made so we could be together, Almira could be here.

Amanda: So this is when Mommy left. And someone's taking pictures of your tears.

Almira: I was really sad. I loved this headband.

Amanda: You understood?

Almira: I don't know. I knew she was leaving and I didn't want her to leave. But I don't know that I knew what was happening really.

Amanda: So when you left for the US, you left Ate in that house, in Quezon City. And so you were saying to me the other day you left her with somebody, someone lived there with her?

Carolina: The people who lived with me were Jiang-Jiang, she was a teenager who looked after Almira, and I think two maids. One usually cooks and the other does the laundry. We didn't have machines. And Nelia David, she was a midwife who worked in my unit, in the psychiatry unit that I ran.

Amanda: So you were saying before that the expectation was that Ate would come join you soon-ish after you left. So – and you had left her in the Quezon City house, but she ended up in Tito Pepe and Tita Lina's house.

Carolina: Tito Pepe got him, and decided it was better that she stay with them.

Amanda: So she just got – he just got her?

Carolina: Yeah, I mean I was here. They just made a decision and whatever.

Almira: I went into their house with their family of five kids and Triccie and I would fight all the time, but we were also best friends, we loved - really, the bulk of my memories of being in the Philippines because when I started to remember are with Triccie, we were so close, we were like sisters, because we were just about the same age. But we also fought like cats and dogs. Like I remember Tita Lina coming in and breaking up our fights. We'd be pulling each other's hair, it was like bad. And she was always the one that had to like make it right, like she would bring me like ice cream, it was like that. I would sulk and pout until she would make it all okay.

Amanda: That's so funny because I don't have any thought of you that way. 'cause you were the older sister, and so you were the one taking care of everybody.

Almira: Right. But for like seven years, I was like an only child. And not only that, but I had sort of this sympathy thing going for me, probably, I’m sure. Although Tita Lina was really strict. And there were moments she wasn't having it at all. I remember sitting at the table with my food, 'cause I didn't finish it. She was like you can't get up until you finish it. And I remember sitting there for a very very very long time. So she was a disciplinarian for sure, but actually I don't remember her being - I remember her being strict, but I don't remember it being, feeling like, oh, I'm so miserable 'cause she's so mean. That was just the behavior that was expected. So she was just that way.

But they really wanted for nothing in that house. I mean, there was a driver that took us to school, they had maids, they had someone to cook their food, and that cleaned up after you. So it was a pretty nice situation. We would go to their country club, go to the pool, that's where I split my chin open. Because we were by the pool and I was running and I slipped - I was running from the pool into the locker room and I fell and I hit my chin and split it open. Yeah, that was bad. I had to get stitches. They had their own little adventures with me living with them. Yeah, they brought me to the hospital.

Carolina: Daddy was sponsored by his boss in Newfoundland who recruited him, Shao nan Huang. Promised him that if he will take the job in Newfoundland, he would work for a kind of visa where he can bring his family.

Atilano: My option was Canada, Australia, those kinds of things. Since Canada was closest, I wanted to go to Canada. But for some reason I only applied in the eastern part of Canada. And the first one I wrote to, Newfoundland, took me, so I said, “oh, good.” But I had, before we got there, I actually had a landed immigrant visa. Which is the same as a permanent resident in the States. Having a landed immigrant visa allowed me to petition direct family. That's what happened with Almira.

Carolina: It was just easier to family reunification of Canada was, they actually practiced it. US had the policy of family reunification but it never happened. They would deny visas. That's why Ate and I were left behind because they would deny visa even if they had supposedly wanted to keep families together.

Amanda: I always thought that when you came to the States, you saw both me and Clarissa like in the Newfoundland airport, like I always had that image that you saw me running around or me and Clarissa running around. But I guess it was just me running around.

Almira: Yeah, I just saw you running around. I remember it clearly because it was, I don't know if it was in a terminal or out by the, but it was a long hallway and I just remember you running up and down the hall. And I was like, all right.

Amanda: This one?

Almira: She’s cute.

Amanda: That’s so funny.

Atilano: Almira had to enter through the United States because that's where I got my landed immigrant status from Boston, and so all of my paperwork was going through Boston. We didn't know anyone in Boston. We knew Tita Fely in New York, we flew her to New York instead so they could have a little reunion there, right? But on the way from New York to Boston, we drove at night, and it was in the middle of a snowstorm. Bad bad bad bad snowstorm. So we were driving in this car, right? And from Connecticut, the good thing was that they had all of the snow plows working that night. So I kind of followed one of the snow plows. So they cleared the highway and I was following them. And then we got to Boston, did the papers, and then, yeah.